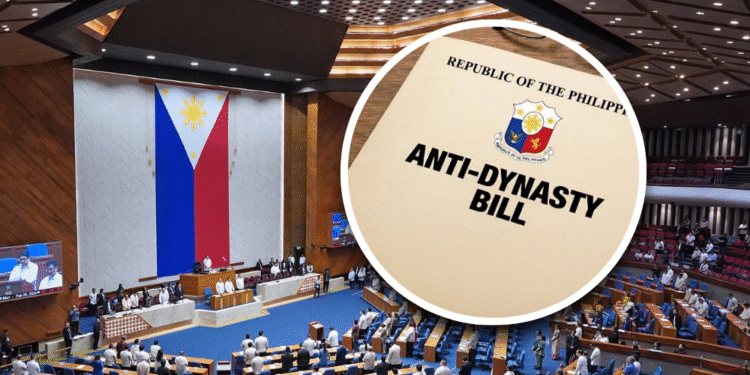

The House committee on suffrage and electoral reforms is moving aggressively to push an anti political dynasty law to the top of its legislative agenda as Congress resumes sessions this January.

Committee chair Ziaur Rahman Alonto Adiong, the representative of Lanao del Sur’s first district, said the ban on political dynasties will be the panel’s priority, citing growing pressure both inside and outside the House of Representatives.

Adiong said there is “clamor” for legislation banning political dynasties not only from the public but also from lawmakers themselves, pointing to the volume of proposals filed in the chamber. He said the House has received 17 versions of anti political dynasty bills, a number he described as evidence of serious intent to finally address the issue.

“On January 27, we will hold the initial discussion and deliberation on the anti political dynasty bill because there is significant clamor. The fact that we have received, if I’m not mistaken, 17 versions on the same subject only shows that the members of the House of Representatives are willing to participate and see an end to all this talk on anti political dynasties,” Adiong said.

The committee plans to convene legal and academic authorities to support the deliberations. Adiong said the panel will invite deans of colleges and law schools, institutional experts, former Supreme Court justices, and one or two framers of the 1987 Constitution to weigh in on the proposed ban.

He also said the committee intends to bring the discussion directly to the public through consultations, arguing that the issue goes to the heart of electoral choice and democratic participation.

“We’re talking about voting rights, and we’re talking about allowing the electorate to choose the candidates. So all of us are stakeholders in this. That’s why pinopropose ko sa leadership is to go down on the grassroots and conduct a public consultation,” he said.

Adiong acknowledged that passing an anti political dynasty law remains legally complex, noting that there is no existing statutory definition of what constitutes a political dynasty and that crafting one acceptable across sectors will be difficult. Still, he said the committee is prepared to confront that challenge head on.

He also conceded that any final version of the bill will be contentious. “Half of the country will not be satisfied,” Adiong said, but he maintained that the measure would withstand constitutional scrutiny if enacted, saying the law would be “constitutionally sound.”

The bills under consideration differ mainly in how broadly they define prohibited family relationships in public office. Most proposals seek to bar relatives up to the second civil degree of consanguinity or affinity, covering immediate family members such as spouses, siblings, children, grandparents, parents in law, and siblings in law. Other versions extend disqualification up to the fourth degree, which would include first cousins, great grandparents, grandnieces and grandnephews, and great aunts and uncles, as well as their marital counterparts.

With hearings scheduled and consultations planned, the House panel is signaling that the long stalled ban on political dynasties is no longer a peripheral reform but a central fight lawmakers are now openly pushing to settle.