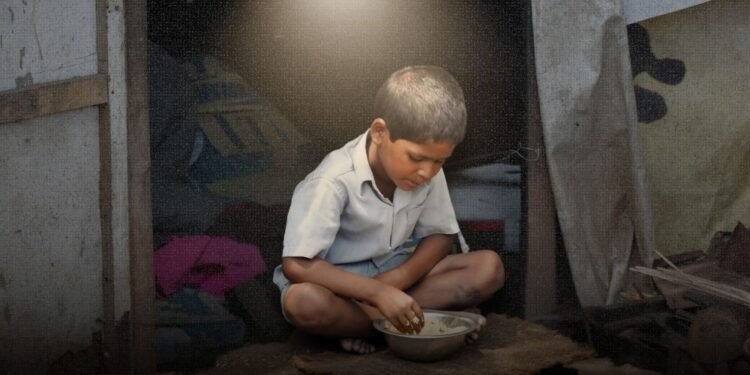

In a country where disasters are seasonal and inflation is a permanent houseguest, “ayuda” is supposed to be the great equalizer. A safety net. A relief system for the vulnerable.

But if you ask around, ayuda in the Philippines rarely feels like that. Instead, it comes with conditions — unspoken rules, political strings, and timing that’s a little too convenient.

It’s not that Filipinos don’t need help. They do — urgently. It’s that the help doesn’t always arrive when it should, where it should, or how it should. And often, it feels like someone else is getting more than their fair share. Ayuda, for many, is still about who you know, not what you need.

So how did public assistance — funded by taxpayers — become something people feel lucky just to receive? Let’s unpack the politics, the programs, and the uncomfortable reality that ayuda is often more complicated than it looks.

The different faces of ayuda

From rice packs during typhoons to cash aid during lockdowns, government assistance has come in many forms. Some of it works. Some of it doesn’t. And all of it has political gravity.

The Social Amelioration Program (SAP), rolled out during the height of COVID-19, was the largest emergency aid operation in Philippine history. Its goal was to reach over 18 million low-income families. But identifying who qualified turned messy fast. Local governments were told to fill the gaps left by outdated national data, giving barangay officials a lot of room — and power — to decide who got ayuda.

On the other hand, the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) was built differently. It’s a long-term conditional cash transfer system tied to health and education compliance, targeting the country’s poorest through a national database. Unlike one-time handouts, 4Ps was structured to be more data-based than discretionary — and largely insulated from politics.

But in 2025, Congress zeroed out the budget for 4Ps, redirecting funds to new programs like Ayuda Para sa Kapos ang Kita Program (AKAP), raising concern that more transparent, rules-based ayuda was being replaced with more flexible — and potentially politicized — alternatives.

Aid with conditions

Many Filipinos understand how the system works, even if they don’t like it.

When relief goods are distributed, who gets them first — or at all — often depends on who you voted for or how close you are to the barangay hall. During the SAP rollout, some communities reported that those with connections received faster or multiple tranches, while others were left wondering if they were even on the list.

It didn’t help that 447 individuals, including over 200 elected officials, were charged for manipulating SAP payouts — from ghost beneficiaries to aid-splitting schemes. The Ombudsman suspended 89 barangay captains in one of the largest mass suspensions tied to a single aid program.

In many cases, assistance is distributed fairly and without bias. But the perception — and sometimes reality — that politics plays a role still shapes how people interact with ayuda systems.

Timing is everything

The controversy around AKAP made headlines when it was included in the 2025 national budget — an election year. With ₱26 billion in funding, AKAP’s scope is wide: anyone earning below minimum wage and affected by inflation could qualify. That covers a huge portion of the population.

The criteria might be inclusive, but it’s also vague enough to allow selective distribution. And that’s the concern. Aid should target the most vulnerable. Instead, programs like AKAP risk turning into a tool for local and national leaders to build support through selective generosity.

A Supreme Court petition has already been filed to review the constitutionality of AKAP, with civic groups arguing it functions like the now-defunct pork barrel system — just under a different name.

The rise of ayuda culture

Beyond the programs and politics, ayuda has become a visible part of Filipino political culture. From tarpaulins on relief goods to politicians handing out rice sacks with their faces on them, the spectacle is hard to miss.

This branding behavior — locally known as “epal” culture — was so widespread that an “anti-epal” provision was included in the national budget to prevent it. But enforcement remains a challenge, and photos of branded aid continue to surface.

The issue isn’t just about narcissistic branding. It’s about reinforcing a narrative that aid is personal, not institutional — that it comes from a politician’s goodwill rather than a public service funded by taxpayers. It repositions citizens as beneficiaries of favor rather than rightful recipients of support.

Short-term relief, long-term dependence

Ayuda can absolutely save lives in times of crisis. It can mean food on the table for the week or rent covered for the month. But when it becomes the main strategy for poverty response, it can create cycles of dependency.

What’s missing in many cases is the shift from relief to empowerment. Livelihood programs, education, access to healthcare — these are the building blocks that help people move beyond needing ayuda in the first place. But they often get sidelined in favor of faster, more politically visible programs.

Experts have pointed out that over-reliance on flexible aid programs reduces the pressure to implement longer-term social reforms. It also keeps aid tied to relationships, not rights.

Reforms will take more than a memo

There are good signs. The government has taken steps to reduce politicization, such as assigning DSWD to handle distribution directly and banning elected officials from physically attending payouts. These are efforts to separate service delivery from political presence — a necessary step if the system is to rebuild trust.

But even well-intentioned programs can stumble if not grounded in strong data and consistent rules. Experts and civil society groups have called for strengthening the national poverty registry, increasing transparency in budgeting, and ensuring that ayuda doesn’t become a workaround for structural underinvestment in core services.

These reforms require more than paperwork. They require political will — the kind that chooses institutional strength over personal gain.

Ayuda shouldn’t feel like a test of loyalty

For most Filipinos, ayuda is not about politics. It’s about survival. Whether it comes as cash, relief goods, or livelihood aid, what matters is that it reaches the right people, at the right time, in the right way.

But when programs are designed or implemented with blurred lines between governance and campaigning, even good intentions can get lost. The challenge is not removing ayuda — it’s deprogramming the politics from the process.

Support that treats citizens as clients, not voters, is possible. A system where help is reliable, fair, and rights-based is possible.

But first, ayuda has to stop being the stage and start being the service.