They leave the country. The money stays.

Overseas Filipino Workers aren’t just family breadwinners — they’re national economic buffers. More than 1.2 million OFWs work abroad annually, and their remittances are the reason the Philippines can survive floods, inflation, and presidents with questionable policies. In 2023 alone, remittances hit a record-breaking $37.2 billion, jumping to $38.3 billion in 2024 — a steady flow of dollars that makes up 8.5% of the country’s GDP.

That money keeps supermarkets busy, schools full, and real estate overpriced. And while foreign investors come and go like flaky Tinder dates, OFWs have stayed loyal. Their money arrives like clockwork — rain or shine, pandemic or not.

The economy relies on homesickness

Every peso wired from abroad fuels domestic consumption — and not in a small way. OFW families spend on groceries, tuition, loans, home renovations, and the occasional iPhone upgrade, making up a significant chunk of consumer spending. That kind of purchasing power drives demand in retail, real estate, education, and banking.

In fact, those dollars matter more than most exports. Remittances beat out foreign direct investments year after year, and they outperform traditional industries in foreign currency earnings.

OFWs even play defense for the peso. Their steady dollar inflows help stabilize the exchange rate and prop up forex reserves, especially when the country’s trade deficit is yawning wider than a bored commuter at 6 a.m.

Other countries export goods. We export labor.

The Philippines has built an entire economic model around exporting people. And it shows. Unlike India or Mexico, where exports or tech services dominate, our most consistent asset is human labor — caregivers, seafarers, nurses, welders, domestic workers, engineers, and entertainers.

As of 2024, the Philippines ranked 4th in the world for remittance receipts, behind only India, Mexico, and China. But while those other countries are busy with global trade deals, we’ve cornered the market on tears at airport departure gates.

And those tears are profitable. Labor deployment brings in more than just money — it comes with geopolitical influence, diaspora reach, and cultural soft power. Filipino nurses became symbols of compassion during the pandemic. Filipino seafarers keep global shipping running. Filipino domestic workers are often the lifeline for aging populations in East Asia and the Middle East.

But here’s the kicker: even with that level of importance, labor protections are patchy at best.

Behind every dollar is a sacrifice no app can track

Let’s drop the economics for a second. The reality is: OFWs aren’t remittance machines. They’re people. And every dollar that lands in a bank account back home carries the cost of distance, silence, and often — pain.

Roughly half of all OFWs are women, and many work in domestic labor jobs where abuse is rampant and accountability is a myth. The kafala system in countries like Kuwait and Saudi Arabia ties workers to their employers, creating conditions where exploitation can thrive unchecked.

In 2023, Filipina housekeeper Jullebee Ranara was brutally murdered in Kuwait — the latest in a string of high-profile cases involving violence against OFWs in the Gulf. And for every story that goes viral, there are thousands more that don’t.

Meanwhile, emotional trauma doesn’t get tallied in remittance reports. OFWs miss weddings, graduations, and funerals. They raise children over video calls. Their marriages strain under years of separation. Their identities blur between belonging and alienation — Filipinos abroad, foreigners at home.

Even after decades of working, many OFWs return broke or sick. One heartbreaking example: in 2019, a former OFW who worked over 20 years in Saudi Arabia ended up homeless in a Manila park, forgotten by both family and government.

The cycle is brutal. Sacrifice for decades, send money home, hope someone remembers you when you return.

Filipino families run on love letters in Western Union receipts

Despite the suffering, there’s one thing the country does well — worship its OFWs in spirit, if not in policy.

OFWs are mythologized in ads, songs, and social media tributes. Surprise homecoming videos rake in millions of views, and every viral tearjerker reinforces the national guilt-and-gratitude complex. Even the state joins the spectacle. The DFA produced a slick video in 2020 honoring OFWs as “Filipinos caring for the world” — complete with cinematic montages and orchestral music.

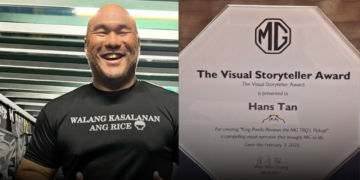

Awards like the Bagong Bayani Awards celebrate “model OFWs,” while July 7 is designated National Migrant Workers Day, where politicians hand out plaques and Facebook posts. It’s all part of the narrative: that OFWs are the modern-day heroes, the spine of the economy, the heart of the family.

But when the music fades, and the airport hugs are over, OFWs still face the same broken systems — inconsistent labor protections, lack of reintegration plans, and weak access to health or retirement services.

The praise is loud. The policies, not so much.

The future economy still has an OFW-shaped hole

Even as the Philippines pushes for industrialization and digital innovation, the truth remains: the economy still leans heavily on remittances.

There’s no clear plan for how to gradually decouple from labor export dependency, and the institutional mindset still treats OFWs as long-term solutions rather than temporary patches.

Yes, financial literacy programs and reintegration schemes are in place — but they’re underfunded, underpublicized, and underwhelming. There’s no robust national pension for returning workers. No clear roadmap for post-OFW livelihood.

For many, retirement looks like more migration — or worse, quietly returning to a country that doesn’t know what to do with them.

As long as local job markets remain uncompetitive and wages stay insultingly low, the OFW pipeline will continue.

The country exports its best and brightest not because it wants to — but because it still can’t give them better options at home.