For decades, Philippine cinema has fought its way onto the world stage, delivering powerful, socially charged stories that have resonated with audiences far beyond its borders.

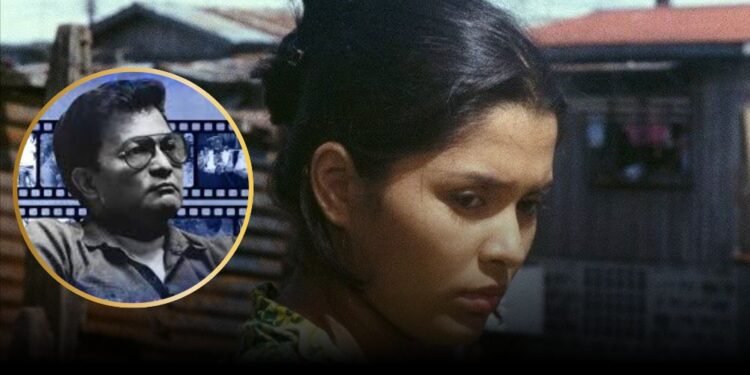

One of the earliest and most significant milestones in this journey was Lino Brocka’s Insiang (1976), which made history as the first Philippine film to be screened at the Cannes Film Festival.

Shown in the Directors’ Fortnight section in 1978, Insiang wasn’t just a film—it was a statement.

Breaking Boundaries: Insiang and Filipino Social Realism

A searing critique of poverty, injustice, and abuse, Insiang captured Manila’s underbelly with brutal realism. It followed the harrowing life of a young woman trapped in a cycle of violence, oppression, and survival.

Brocka, known for his fearless storytelling, painted a bleak yet powerful portrait of urban hardship, one that resonated deeply with both local and international audiences.

It remains one of Brocka’s most celebrated works, frequently listed among the greatest Filipino films of all time.

Before Insiang was embraced by Cannes, it had already made waves in the local film scene. The film won the Gawad Urian Award in 1977 and also earned multiple honors at the 1976 Metro Manila Film Festival.

This recognition solidified Brocka’s place as a master filmmaker who dared to confront societal issues that many preferred to ignore.

Filipino Cinema’s Early Triumphs

Yet Insiang was just one of many Filipino films that carved out a legacy of excellence. Decades before Brocka’s breakthrough, Manuel Conde’s Genghis Khan (1952) made waves as the first Asian film to be screened at both the Cannes and Venice Film Festivals.

Unlike Insiang, which was deeply rooted in Filipino realities, Genghis Khan was an epic retelling of the legendary Mongol conqueror’s rise to power.

Its grand scale, innovative storytelling, and ambitious production values caught the attention of European audiences, proving that Filipino filmmakers could craft stories that appealed on a global level.

But where did all of this begin? The very first Filipino-directed and produced feature film was Dalagang Bukid (1919), directed by José Nepomuceno.

At a time when Hollywood dominated cinema, Nepomuceno’s film was a groundbreaking achievement, proving that Filipinos could tell their own stories on screen. Although Dalagang Bukid has long been lost to time, its impact remains undeniable.

It laid the foundation for an industry that would eventually stand shoulder to shoulder with the world’s best.

A New Era of Global Recognition

While Brocka and Conde helped establish the Philippines’ cinematic presence on the international stage, Brillante Mendoza took it to the next level. In 2009, Mendoza became the first Filipino filmmaker to win Best Director at Cannes for his film Kinatay.

The film, which depicts the gruesome underworld of Manila’s crime syndicates, was divisive—it stunned critics with its raw, unflinching violence. Some hailed it as a masterpiece; others found it too disturbing. But one thing was certain: Mendoza had made an impact.

Winning at Cannes is no small feat. The festival is notoriously selective, with thousands of films vying for a slot every year. For Mendoza to clinch Best Director proved that Filipino cinema wasn’t just about competing—it was about dominating.

The Future of Filipino Cinema on the Global Stage

The success of Insiang, Genghis Khan, Dalagang Bukid, and Kinatay paved the way for a new wave of Filipino filmmakers who continue to push boundaries.

Directors like Lav Diaz, Erik Matti, and Raya Martin are carrying the torch, experimenting with storytelling techniques, breaking conventions, and challenging audiences.

With streaming platforms making international distribution easier than ever, Filipino films are no longer confined to local audiences.

Movies like On the Job (2021), BuyBust (2018), and Die Beautiful (2016) have gained critical acclaim abroad, proving that the hunger for bold, unapologetic Filipino storytelling is stronger than ever.

From silent films to internationally recognized masterpieces, Philippine cinema has come a long way.

And if history has shown us anything, it’s that Filipino filmmakers will continue to fight, innovate, and tell stories that the world needs to see.